This is an introduction to tradition of Buddhist Yogis, by Pema Khandro. They are also known the Ngakpas and Naljorpas of Tibet. (Tib. sngags pa, rnal ‘byor pa). These are Tibetan Buddhist Yogis of Vajrayana.

An Introduction to the History of Buddhist Yogis

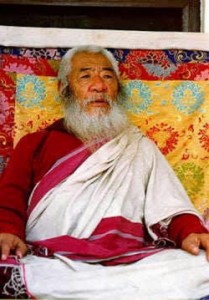

Buddhist Yogis are the ordained clergy of Vajrayana Buddhism. Their robes are just like the robes of monks and nuns but in their traditional form they keep their hair long and wear a white skirt and red and white shawl instead of the maroon skirt, maroon shawl and shaved heads of their monastic counterparts. However due to the diversity of Tibetan Buddhism, sometimes Ngakpas wear the red and white shawls and maroon skirts, or even civilian clothes plus the red and white shawls.

These Buddhist Yogis are Tibetan Buddhists whose practice is based on the notion that the world has as its foundation, wakefulness and natural goodness.

Buddhist yogis of Tibetan Buddhism are non-celibate and do not renounce the material world. Many people think of Buddhism as made up of monastics and lay people. However, this is not a historically accurate image of Buddhism.

Not all serious Buddhists practice celibacy or lived monastic lives. For example, Japanese priests marry and their spouses may have even played a role in caring for the temple. In Tibet, in addition to monks and nuns, there were other vow-holding religious specialists known as Ngakpas and Ngakmas, Naljopas and Naljormas. They have also been described by many other term as well such as gomchens “meditators.” These were not “lay” people though earlier modern scholarship often mistakingly describes them using this term. Since “lay person” refers to non-specialists, this is not the correct term to use to describe these religious leaders. (1) Like their monastic counterparts, they carry life long vows and underwent Tantric ordination, representing a tradition of Buddhist clergy based on Buddhist Tantra and great perfection, “dzogchen” (Tib. rDzogs chen) teachings and lifestyle.

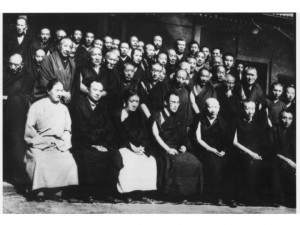

These yogis, like their monastic counterparts, historically have also served as teachers, spiritual leaders, ritual specialists and contemplative practitioners who practiced alone, in small communities or in service of their local villages. They were often married, had families as non-celibates. In the Nyingma lineage of Tibetan Buddhism, there were many such Yogis and because of this, the inclusion of women and appreciation for the power of relationships between men and women were part of its tradition. However there were Buddhist Yogis in all the major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The Kagyus were also well known for the proliferation of yogis. At one point in history the Drukpa Kagyu were said to make up half of all clergy. Even the head of the Sakya tradition has always been a Ngakpa, a Buddhist Yogi, who in the case of the Sakya line, continues the lineage through family bloodline.

Padmasambhava

Historically speaking, Buddhist Yogis practiced largely outside large institutions in local settings, serving their communities as teachers of Buddhist philosophy, doctors, ritual specialists and meditators. Because of this, historically they represented great diversity in Tibetan Buddhism cultivating local traditions according to local customs and family lineages.

The history of Ngakpas is known mostly in fragments since they often lived outside large institutions. Since large institutions were responsible for textual reproduction and dissemination, the history of smaller and non-institutional groups have been more difficult to study. However some major figures in Tibetan history were Ngakpas and their were credited in playing decisive roles in Tibetan history. After the decline of the imperial period in Tibet during the times known as the dark age in Tibet, the Tibetan Yogis were credited with maintaining Buddhism in Tibet. (2)

Other parts of the Buddhist Yogi’s history come through the more influential figures. For example, the founder of Tibetan Medicine, Yutok Yonten Gampo was a ngakpa, as was one of the greatest Dzogchen masters of all time, Longchenpa and the influential 18th century teacher, Jigme Lingpa was also a ngakpa.

Literature also describes the journey of female figures who fully engaged Buddhist teachings while living a non-renunciate life. A nineteenth century yogini, Sera Khandro, tells the story in her autobiography of choosing to be a ngakma, a Buddhist Yogini, following the non-celibate path. This was because she saw romantic love with another Buddhistteacher as the key to her Buddhist practice. One of the greatest and most influential Buddhist masters of modern times was Dudjom Rinpoche who was also a ngakpa. He wore the ngakpa’s characteristic robes of the white skirt and long hair and was married and had children.

The practices done by the Yogis of Buddhism are drawn from philosophical Buddhist teachings such as the great perfection, ‘Dzogchen,’ teachings (Tib. rDzogs chen). They include somatic practices and meditations which informed Tibetan Yoga and Inner Tantra as well as Buddhist rituals from Vajrayana.

At some points in Vajrayana history the ngakpas were rumored to be merely ritual specialists or renown as magicians. This comes from various factors. This reductionist way of describing Buddhist yogis arose due to competing interests in the Tibetan religious landscapes, which did not always frame the groups outside the author’s own sect or institution in favorable light. However when we glimpse a wide variety of sources it is clear that Yogis proliferated the Buddhist landscape and some of the most influential and respected masters of Buddhist history were Yogis. They have also been associated with magic. This is connected with a pan-Tibetan cultural practice of ritual, belief in magic and prayers which permeated all traditions but was more heavily associated with Buddhist tantra. That theme is evident in legendary narratives which described the esoteric activities of these practitioners in more supernatural characterizations, however we can see that such characterizations in legends may not have reflected the life stories of people during their own times and instead reflect common themes in asian narrative practices themselves. Taking a closer look it is clear that rather than being magicians or mere ritual specialists they played wide variety of roles ranging from the philosophical to the contemplative.

Among the Ngakpas one of the greatest philosophical movements of Tibetan Buddhism was carried – Dzogchen, the great perfection teachings know as “philosophical Buddhism,” and its correlate the Mahamudra teachings. Such teachings which undermined institutional authority and promoted the notion of every person having a full blown Buddha nature, already enlightened from the beginning. These teachings were controversial at the time. Yet Ngakpas such as Longchenpa developed these philosophical assertions with a sophisticated degree of meticulous care in response to the dynamic landscape of Tibetan philosophy in the fourteenth century. Ngakpas have practiced Tibetan Buddhism in its full range of practices, some as philosophers, teachers, treasure revealers, yogis practicing esoteric techniques and even scholars.

Today the Ngakpa tradition manifests in varied ways depending on the lineage and teacher. The most visible aspect of the Ngakpa tradition is the red and white shawl. The monastic practitioners were maroon shawls whereas those in the ngakpa traditions where red and white shawls. In my travels I have seen a great variety of how this is manifesting in North America. In some North American communities, students are given Ngakpa shawls after students have completed ngondro, or three year retreat or longer periods of serious study. In other situation Lamas where the shawls along with the monastic red skirts to show they are non-celibate and in some cases are not necessarily identified with or focused on the Ngakpa tradition per se. In some cases of smaller groups, the red and white ngakpa shawls are given by Lamas to their students to note serious practitioners who are non-celibate but not necessarily ordained practitioners. In other cases Ngakpa ordination is given which includes the fourteen vajrayana vows. Yet there is also diversity in who takes these vows since in addition to being part of Ngakpa ordination they are also part of high level Vajrayana empowerments. So others take these vows as part of Vajrayana empowerments but it does not necessarily include Ngakpa ordination. So the situation is quite varied and diverse from lineage to lineage. A standardized education system or education level has not been established. However this diversity is not unique to the Ngakpa tradition, it is the hallmark of Tibetan Buddhism, which due to its landscape and longevity, fostered variety. How the tradition will arise in the future is yet to be determined.

Why the World Needs Ngakpas

The Ngakpa tradition is important for the future of Buddhism. Especially in North America where there has been widespread disillusionment with celibate religious and institutional authority. We have witnessed countless stories of sex-scandals among asian religious teachers – having a group of religious leaders who are married, vow-carrying and ethical offers a positive example of spiritual and ethical leadership in a world where those lines need to be clear. Positive examples of non-celibate, non-hedonistic religious practice by clergy who are ethical and compassionate is valuable and necessary. Likewise, positive examples of male and female relationships in the Buddhist context are of great value. We have also had a disillusionment with large scale institutions and the character of these Ngakpa traditions has always been smaller, local and personal, providing a platform to resolve the alienation our culture feels with religion through a direct encounter with something much more personal. In smaller settings, authentic spiritual development is possible. Potentially, with the presence of both large scale Buddhist institutions and smaller religious communities and Tibetan micro-cultures, diversity can survive and dogma can proliferate less. Finally because the Ngakpa tradition has a long history of male and female practitioners it offers a history, literature and philosophy that is relevant to male and female practitioners. Buddhism outside institutions developed brilliant resources for a very direct access to spiritual experience and philosophical inquiry. Such practices are tailored towards the complex lives of people with jobs, families, children, it offers resources that a purely monastic celibate Buddhist lineage does not.

Yet both these clergies are necessary, we need monastic and non-monastic Buddhist clergy in the future as well as a large population of lay practitioners. Institutional and non-institutional forms of Buddhism have their roles. One does not cancel out the other and that is why they have both existed throughout the Tibetan Buddhist history. It is particularly important that we see continue to see the return of full ordination of Tibetan nuns in Tibet so that these ancient traditions of Buddhism can continue to develop to include women in all its levels of authority and leadership. So in my mind I see the future of Tibetan Buddhism in America being carried by monks, nuns, ngakpas and ngakmas. This will offer the variety of leadership needed for the tradition to flourish and nourish the needs of those who draw on Buddhist wisdom.

For more information about the Ngakpa tradition and courses about its history and practices visit Ngakpa.org

You will find answers to frequently asked questions about practice and study with Pema Khandro here.

(1) Van Schaik, Sam (2004). Approaching the Great Perfection: Simultaneous and Gradual Approaches to Dzogchen Practice in Jigme Lingpa’s Longchen Nyingtig. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-370-2.

(2) Rinpoche, Dudjom (2002). Eds, Dorje, Gyurme and Kapstein, Matthew. The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism; Its Fundamentals and History 2nd Ed. Wisdom Publications.